A year ago, I remember telling a dear friend that the age of agents wasn't here yet - the signs were yet to come. There were no agentic systems that were reliably useful, nor were there any that were (even inconsistently) superintelligent.

Today both of those things are true. Deep research is an irreplaceable part of modern work, and Claude Code in the right hands can do amazing things.

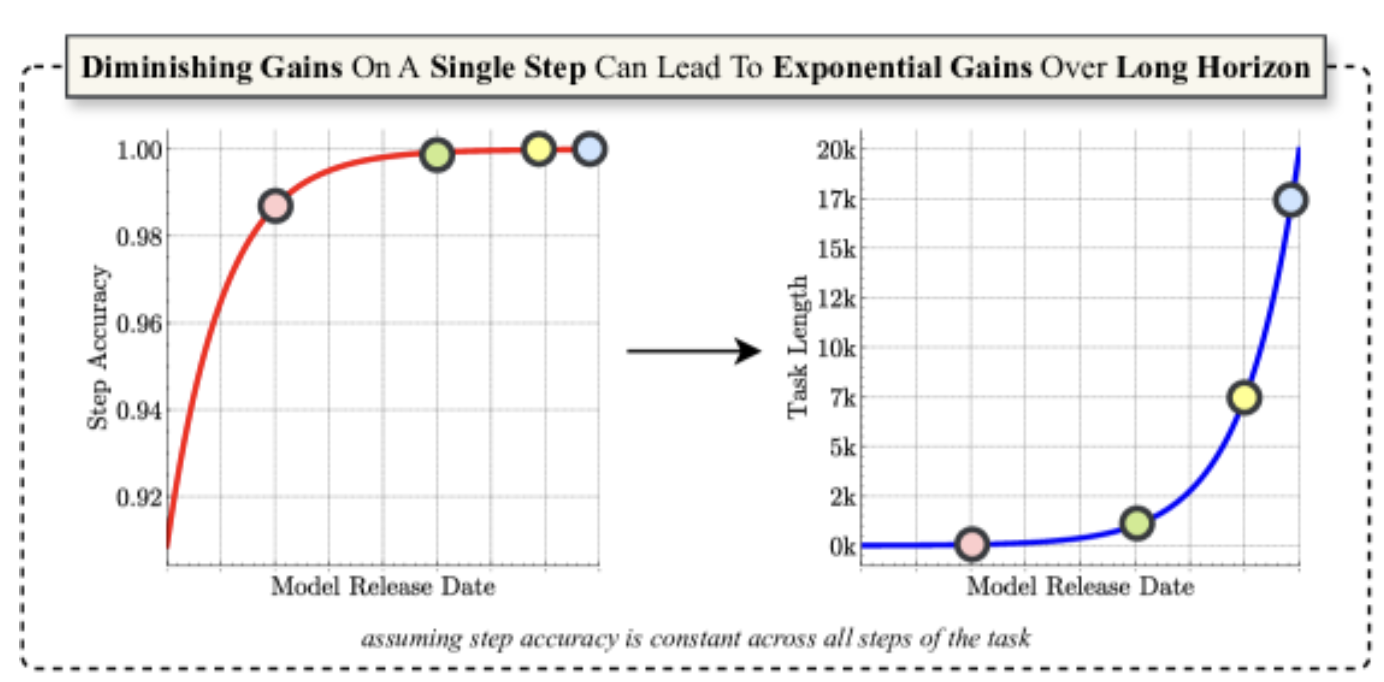

It might look like benchmarks and single-turn intelligence is starting to plateau, but we're racing ahead on a completely new frontier: task horizon11The Illusion of Diminishing Returns: Measuring Long Horizon Execution in LLMs1The Illusion of Diminishing Returns: Measuring Long Horizon Execution in LLMs.

As we wrote before, the era of the LLM call as the base primitive is coming to an end.

The problem is no longer "How do I get this model to respond the way I want", but "How do I keep this agent from tearing itself apart after a hundred loops?"

The embers of AGI

Intelligence is stochastic and inconsistent by nature. Humans are the perfect example - it takes incredible effort for us to do the same thing the same way twice (something a lot of our sports are built around). Turns out LLMs function the same way.

When constrained through current agentic systems, this inconsistency shows up as brittleness: random, weird bugs and an inability to extend the task horizon past a few hundred turns. Task horizon - the length of time a task can be productively worked on - applies similarly to humans. Path dependent failures plague repeated runs, crash systems and bury confident mistakes deep inside large projects.

If we are to ever place agents at the bottom of our stacks - to be the first mile workers for data, human interfacing or development - we need them to be a lot more reliable.

How do we build long-horizon agents that can function for days, while maintaining the same unit output of productivity?

Learning from ourselves

The good news is that we've done it before. It took us a few thousand years, but we've figured out ways to take inconsistent humans with sick days, lives and build consistent reliable systems.

I don't worry that the supermarket will be open tomorrow, or that the tax department will chase me for my payments.

We've managed to figure out productive human systems (organizations if you will) that are more reliable than the least reliable humans inside them. We did this; not by fixing human inconsistency but by building structures that can channel it. The best organizations on the planet benefit from this inconsistency by channeling it into innovation and creativity.

We can do the same with AI.

This is a guide on what we did to build Antibrittle Agents at Southbridge: agents that benefit from randomness, while being resilient to problems on smaller timescales. This took us the better part of a year (and seven approaches), but we can now run productive agents that can take hours or days to mine complex datasets to build increasingly dense representations for use in ageing science, agentic search, financial data reconciliation, the list goes on.

In the next few weeks we hope to release Strandweave runtime - the underlying runtime that powers most of the work at Southbridge, designed around our opinions on making reliable agents. This is a collection of those opinions, along with everything we had to unlearn.

Background

This is the fifth in a series of posts trying to put down the things I've learned, as I repeatedly climb out of the Dunning-Kruger trap of thinking we know how to use these things:

- Everything I'll forget about prompting are the things I had to unlearn about single-turn prompting and task complexity.

- How will matrix multiplication.. was about the rising fear of increasing model intelligence.

- Better RAG 1-3 and the Rich man's guide to RAG made the (then) controversial statement that agentic search would win over the embed-everything-all-the-time approach.

- Everything I'll forget about evals made a number of (then) controversial arguments about why eval platforms at the wrong time can be harmful.

Each time - same as this time - my hope is to put down everything I know about a new frontier we're all educating ourselves on.

So once more unto the breach, dear friends: we'll structure this one as a list of agentic heresies and their implications. An agentic reformation, if you will.

We'll use examples where possible. For the time being, we'll use Deep Research and coding. These are ideal because they're debatably the easiest disciplines22The rise of Cognition2The rise of Cognition for useful agentic work today, and also the ones we're most familiar with. If our propositions hold there, they'll hold in domains that are messier and harder to validate.

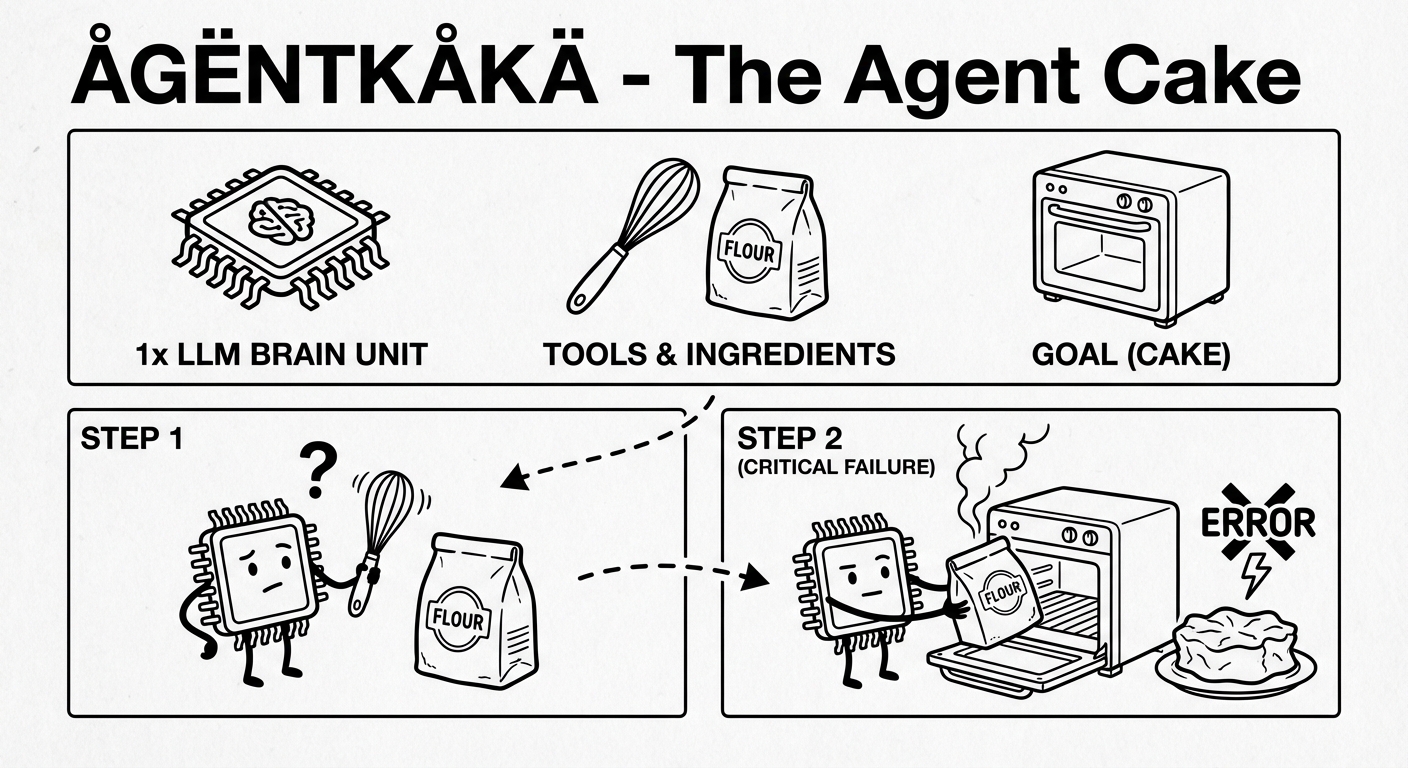

Let's start with a short definition for an agent: An LLM in a loop with tools and a goal.

Example: "I'd like a cake, here's an oven and some flour."

The goal in this context is what establishes the horizon, which has been a useful didactic instrument for us to separate simple problems from the complex ones. Horizon can be defined as time taken, if some measure of productivity is held constant.

If you could work at the same constant rate, something that would take ten days is a longer horizon task compared to what can be accomplished in one.

Here's an example:

- A single LLM call can find relevant information from a book or a paper, needle-in-the-haystack style. We might call this ultra-short horizon.

- A short-lived agent that could work consistently for a minute (or ten calls) can find relevant information from multiple web searches and combine them into something more useful. We'd call this short horizon.

- A longer-lived agent could take twenty minutes, and visit references from each page, follow links, follow trails and investigate before compiling a write-up. This could take hundreds of LLM calls. Medium horizon.

- A long-horizon agent - armed with the ability to make thousands of calls over hours and manage billions of tokens of context - could understand the question in more detail, collect sources, look up authors to study intent and bias, rewrite relevant parts to account for bias, reframe the question as more information is known, run simulations or deterministic code to aggregate numbers, and structure a final report that best matches the question, and generate graphics to match.

Task horizon grows as the problems we're willing to give agents get harder and harder.

Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp,

Now that we have definitions in place, let's get into it.

Heresy 1: Solutions aren't sequences of successful steps.

This is the one that held me back for the longest time, and the one that took the longest time to unlearn. Our platonic ideal of an agent is one that makes no mistakes. Our ideal of an agentic run is one that has the most successful toolcalls and responses possible.

This is false. I'm not sure how we got here; maybe we still see LLM programming as parallel to computer programming, or perhaps we see our ideal humans as those that make no mistakes.

The easiest way to prove this is to record yourself (or someone else) working on a complicated problem. We make tons of mistakes. We retrace our steps, a lot. The ideal case isn't that mistakes don't happen, it's that each false path teaches us something new, uncovers a new approach. Complex work is barely a sequence of steps.

Real-world problems branch and break into feasibility checks, sub-problems, experiments, research, and many other subtasks that affect each other in non-sequential ways.

To use coding as an example, this comment (from Joseph Trasatti, one of the Codex developers at the Reddit AMA) comes to mind:

My favorite way of using codex is to prototype large features with ~5 turns of prompting. For example, I was able to build 3 different versions of best of n in a single day. Each of these versions had a lot of flaws but they allowed me to understand the full scope of the task as well as the best way to build it. I also had no hard feelings about scrapping work that was suboptimal since it was so cheap / quick to build.

This is not an isolated pattern - most of my own work mirrors this repeated experimentation, push-forward-and-reset, multi-path approach.

Another example is the post you're reading - which took me eight versions - two outlines, and a couple of weeks.

On the outset, the task is simple: What is the best sequence of words that communicates these ideas?

Version zero was a loose collection of notes, recordings, quotes and thoughts. Version one had three different openings. By V2 I had written two new ones, which now made five. V3 ended up becoming a completely different post, and V4 was the first in-thread fleshed out version of all the things which pointed out just how much didn't belong in this post. V5 had a locked introduction and a smaller, slimmer outline. V6 and V7 were better, from-scratch rewrites that slowly looked less like a collection of things and more like a single piece.

V8 rewrote everything once again so that we didn't flit between active and passive voice, with shorter sentences and easier transitions.

The point I'm making is that there was no successful string of tool calls to get from my starting point to what you are currently reading.

If I could somehow represent my actions as an agentic log, there were more failures than successes.

To solve the larger task, I had to work on multiple problems almost simultaneously.

- What is the best way to open?

- What is the appropriate amount of background and what is it?

- What is the core narrative thread?

- What links and references provide appropriate context?

- What am I trying to say?

Every word I wrote or reference I read changed my progress and state on all of these questions all at once. Some of them could be said to have a higher priority or surface area than others, but there is definitely no order to speak of. You might solve the last question first, but you could find a really good article, paper or reference that changes your mind about what the piece is really about.

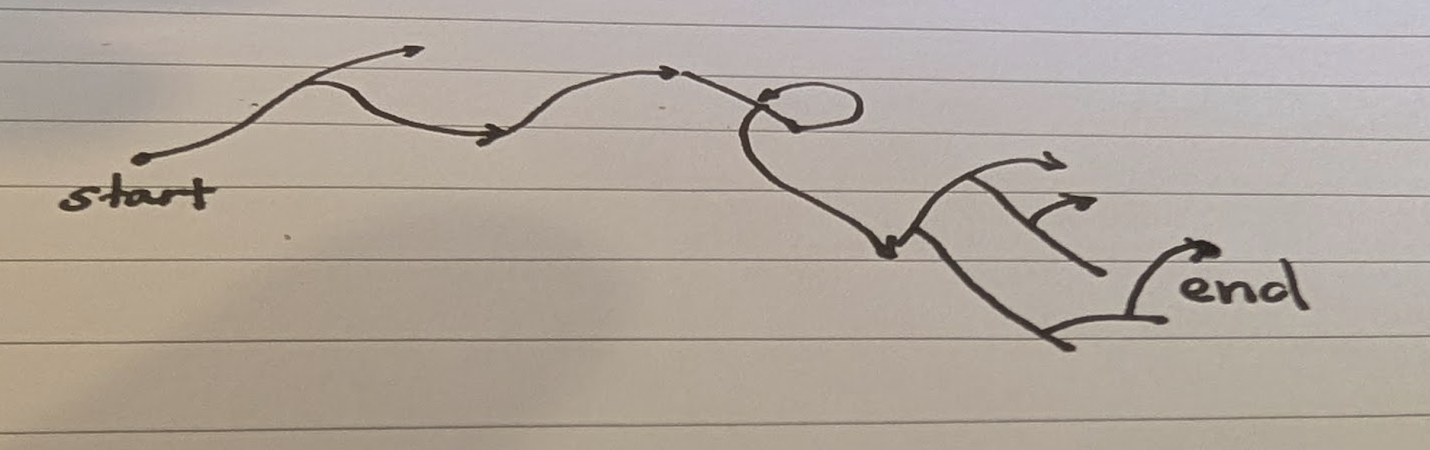

This is what we think problem solving looks like:

Meanwhile this is what it actually is:

Minus the ability to see the maze.

I hope you didn't mind me repeatedly belaboring this point, but it's the central pivot for changing our thinking about agents, especially considering Heresy number 2.

2: Forcing agents to operate in successful sequential microsteps makes them brittle.

This is also difficult to realize, when most of our work in agents today goes into TODO-listing agents (and repeatedly reminding of their TODOs), Plan-Act separations, and hundreds of .md files trying to outline tasks before they've even started. The first one of this kind I remember using was the sequential-thinking MCP. I remember thinking it was a good idea, but something felt wrong about the sequential part even then.

Are we shoving larger and larger round pegs into square holes?

The problem is that progress is non-linear on large tasks, and subtask division is often unknown at the start. TODO lists impose a false linearity which hurts more than it helps. They force the component sticks of a problem into a straight line, instead of something load-bearing that fits the task.

Knowing when tasks are completed (or partially progressed on) is a problem that even humans have trouble with. We've created a 9-10 figure industry of books, speakers and courses trying to sell you solutions to this problem with t-shirts, story points and so much more. Asking our agents to one-shot what we still can't solve seems downright mean.

This is why humans are still the best agentic orchestrators. We can hold sub-problems in mind, redirect agents to other problems, communicate context, and let sub-agents focus on specific threads while maintaining global progress. This is a tall order within the intelligence and context windows of models today. If you're interested, this is a detailed exploration (with real examples) into orchestration patterns with and without the human as the central manager of information.

It's good for job security, but at scale this is a problem. Even if we were all willing to be slaved to our agents all the time, the sheer amount of intermediate tokens and time involved in a long task (hours or days, millions or billions of tokens) makes it near impossible for a human to function as the orchestrator.

3: Adding more agents to a problem makes it later.

If we're having fun paraphrasing Brooks:33Brooks's law3Brooks's law

What one agent can do in ten minutes, twenty agents on a Kanban board could do in two days.

Wait - didn't we just say that most large tasks aren't sequential? Surely more agents could solve our context problems, increase the amount of test-time compute and get us closer to AGI?

Unfortunately they also aren't embarrassingly parallel. We learned this lesson with CPU cores in the early 2000s. Starting with the megahertz myth in 2002, rising core counts ("The free lunch is over") eventually ended with us realizing that more cores (read: agents) does not mean faster programs. In other words, "Concurrency is not parallelism".

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once.

Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.

A very small regime of tasks (like the initial parts of deep research, or spreadsheet filling) lend themselves to parallelism, where each subtask does not need to be aware of the other ones. Count yourself lucky if your chosen problems land in this regime, but most of them aren't in there.

With most tasks, parallelizing them would mean exponentially increased sibling communication load (information exchanged between agents at the same level). Subagents need to communicate a lot more; not just in update-passing, but updating each others' trajectories or even suggesting murder-suicides when new information comes in. Managing sibling communication is nontrivial: too little, and you get confident hallucinations (see the orchestrator article above for examples). Too much and you don't have enough left to work.

I might go far enough to argue that the parallel subagent victories we're seeing on frontier benchmarks don't translate to the real world. Benchmarks are - by definition - comprised of hard to do but easy to verify problems that can be gamed with compute. Once you build a verifier, picking best of n is an easy way to scale up scores.

In most cases, focusing on single-thread (read:agent) performance yields significantly better results. The only exception I've observed is when you want to trade compute for time non-linearly. For some problems, you can throw 10x the compute at something for a log decrease in time taken.

4: Agents are limited today by our ability to reason about their behavior.

Meta-reasoning is the bottleneck, and the thing that often causes brittleness (meta-reasoning here is a meta-phor for the problem being you). Yes, you - the human in the loop, the ghost in the shell - is likely the thing holding back agent performance.

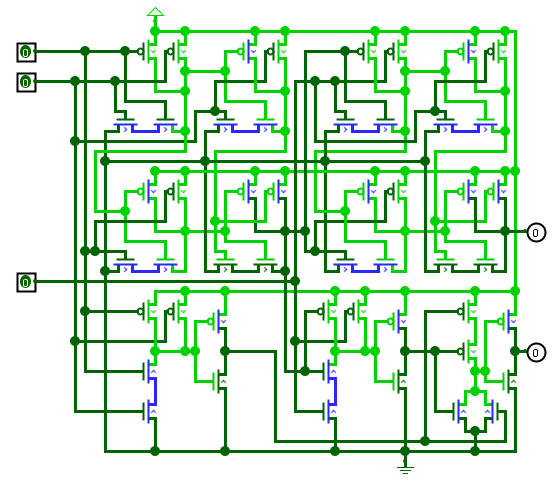

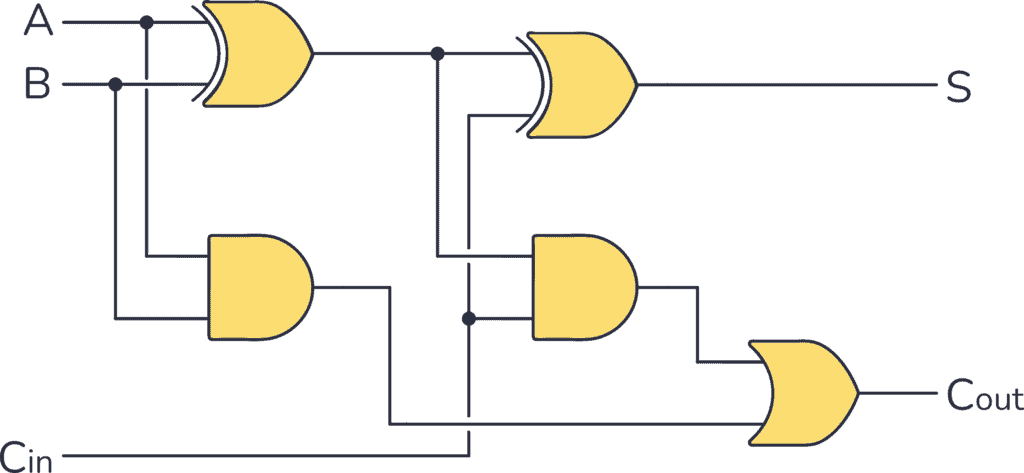

When this happens, abstractions are often the culprit, and the solution. Without the right abstractions, it can be hard to tell what something will do, or where it will go.

Which of these is easier to trace through and understand? Which one is easier to modify?

; Assume array pointer in RDI, length in ESI

inner_loop:

mov eax, [rdi + rcx*4] ; Get arr[i]

cmp eax, [rdi + rcx*4 + 4] ; Compare with arr[i+1]

jle no_swap ; If less or equal, jump past swap

; --- The Swap Logic ---

mov edx, [rdi + rcx*4 + 4] ; Temp store arr[i+1]

mov [rdi + rcx*4], edx ; arr[i] = arr[i+1]

mov [rdi + rcx*4 + 4], eax ; arr[i+1] = original arr[i]

mov BYTE PTR [swapped_flag], 1 ; Set swapped = true

no_swap:

inc rcx ; i++

cmp rcx, rsi ; Compare i with (n-1)

jl inner_loop ; If i < n-1, loop again

function bubbleSort(arr: number[]): number[] {

let n = arr.length;

let swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

for (let i = 0; i < n - 1; i++) {

if (arr[i] > arr[i + 1]) {

// Simple swap

[arr[i], arr[i + 1]] = [arr[i + 1], arr[i]];

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

return arr;

}How about here?

This is often the reason that no-code tools find strong audiences, despite the insistence of engineers like us that they will never be as powerful as code. There are acknowledged problems with higher abstraction levels, but the right ones can be useful. Moving from Assembly to C and then to Arduino felt like a complete loss of control for me during the 8-bit days, but even I had to admit that I could reason about longer and longer programs without worrying about Endianness or bit flips.

At least for today, Agents are designed by humans, implicitly or explicitly. The core takeaway for me was that our current method of creating agents - humans in the loop peppering mini-prompts in conversation with the agent that is both being built and is doing the work - is the worst way to build reliable agents.

This is why we have the wizard gap - as Gemini called it when reviewing this article. Some people can do crazy things with agents, and some of us are convinced they can't even rename a file without making mistakes.

The things we did

Before we go into solutions, let me give you a little more context about us. The goal at Southbridge has been to solve the data problem: Information is recorded in a context that is separate from that in which it will be retrieved. Bridging these two contexts at human-scale data requires deep indexing, unification, flattening - almost every tool for transformation at our disposal.

We also need agentic systems that can use these tools in complex ways without getting lost.

If we can solve these things, we can get to Data General Intelligence: AIs that can function as interfaces to any size or shape of information.

Working through this problem, we have a number of requirements imposed on us due to the sheer scale and heterogeneity of human data.

- We need agents that can handle incredibly large volumes of data. Being able to efficiently crawl and map large new data requires new solutions for the management of context, and good retention and handover of agentic intermediates.

- We need reliable, bottom-of-the-stack agents that can toil unsupervised for hours mining information without breaking or complaining.

- We need to be able to stack agentic behavior without increasing brittleness.

- We need to work at abstraction levels where our team - limited to about 350 billion neurons - can reason about, debug and improve our agents.

Here's what we did.

Run boxes

The first and most useful thing has been to swap our core primitive from a single LLM call to an agentic loop.

This change in abstraction makes a big difference, not unlike swapping registers in Assembly for variables in C:

- Registers are tied to an exact memory location, variables can be stored anywhere.

- Registers are fixed to a specific bit-width, variables can hold different sizes.

- Registers have a limited set of operations, variables can have operations defined by data-type, and in later languages by content.

In the same way, working at the level of abstraction of an LLM call means being limited to success or failure on that singular call. An agentic loop on the other hand can fail in the middle, recover and still arrive at a good result. New operations for managing agentic trajectory open up at higher levels, as well as tool operations with combined results on things like the file system; things which are hard to observe at the single call level.

An LLM call is judged simply on the response, whereas the concept of behavior emerges at the level of an agentic loop - a very useful property that can allow for modifications to the entire run.

Rice cookers figured this out a long time ago: The only way to measure progress and success on stochastic systems is through behavior instead of immediate state. As an example, temperature spikes (as water boils away in pockets) don't mean that a cooker exploded.

Similarly, rocket testing can use start and run boxes - operating ranges of behavior aggregated from signals - to measure success and distance to catastrophic failure at each stage of operation.

In our case, we can ask two simple questions to get started:

- What do we expect to see when things go well?

- What do we expect to see when things go badly?

The best AI engineers I know do this intuitively with coding agents - they watch every line of output, but a single failure isn't reason to aggressively jump in and redirect. The best managers I know do the same thing. How do we confer the same human intuition about when to intervene and codify it in a harness?

Regions of freedom

There are two problems here we want to solve, both of them imposed by our current model of agentic execution (see Heresy 1 and 2).

- We want our agents to be eventually consistent without imposing specific parameters of success at each individual LLM call.

- Problem solving involves both executing on solutions and finding new solutions to execute on.

The second, also known as the exploration-exploitation dilemma, is well known in Reinforcement Learning. The difference in our case is that we have a significantly more complex system working in real-time, with much harsher requirements.

The solution here might lie in thinking about subproblems instead of subtasks. Let's use Deep Research as the example, once again. Mark....

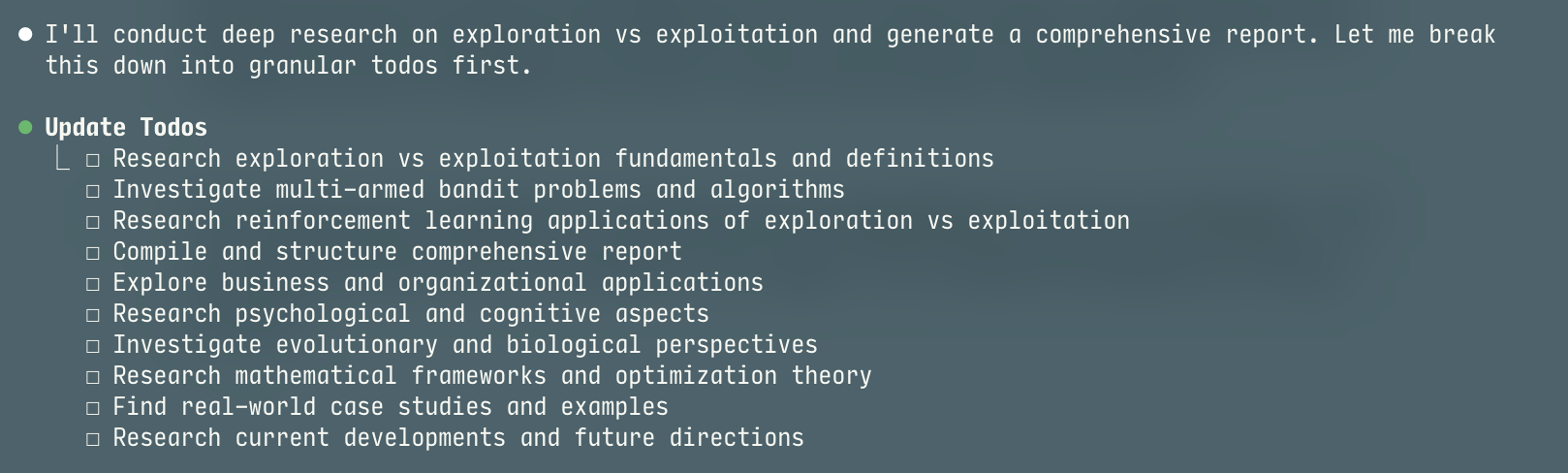

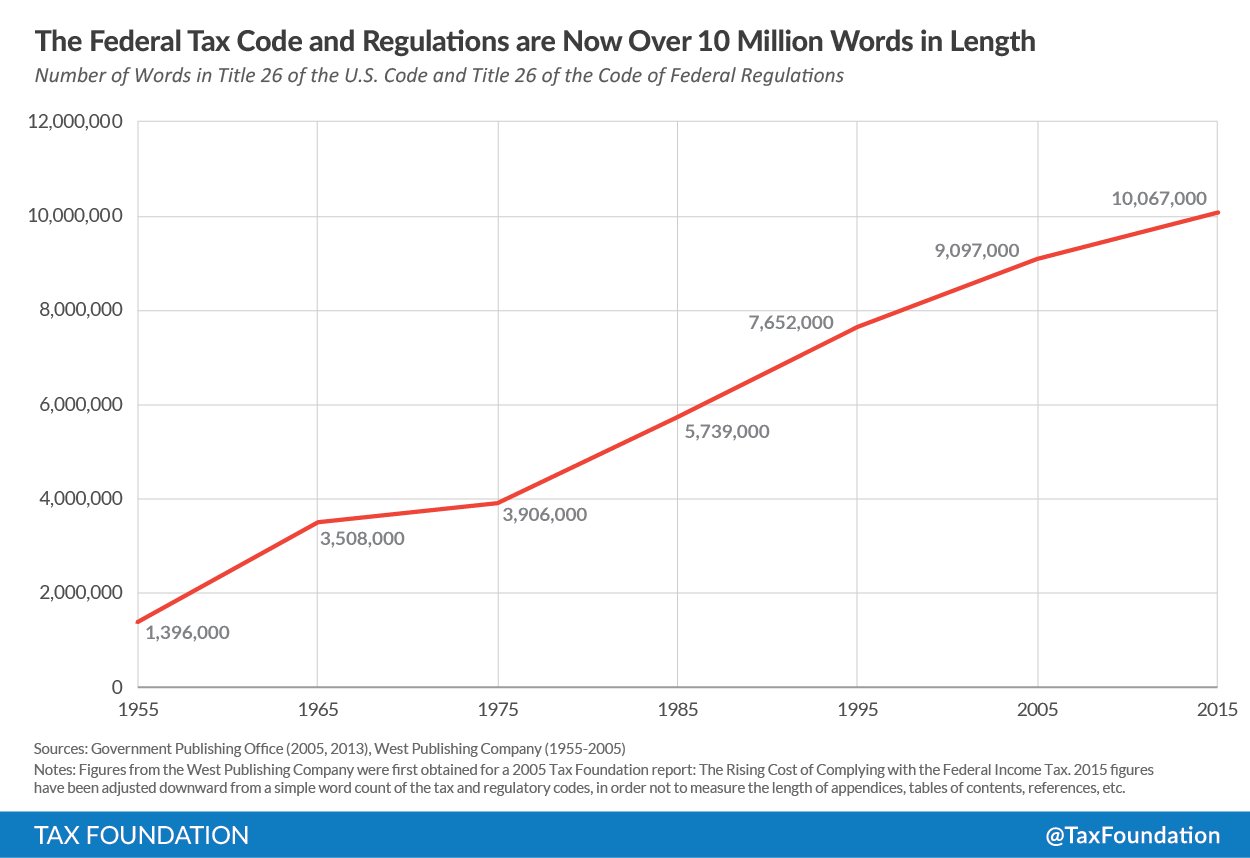

For fun, here's CC breaking down a deep research task into TODOs:

Here's CC again, breaking down the same task (same prompt) with information from this article above the Mark:

It's not fully there, but it's a step in the right direction. The first set of TODOs - in their very formulation - linearize tasks that are interdependent, baking in assumptions about the task itself.

The second set outlines problems, which make the stochastic nature of progress a lot more clear.

At the meta level, a better formulation of the subproblems in deep research might be:

- Expanding the input into a research task comprised of knowledge to collect

- Creating appropriate search queries given previous queries and research tasks

- Process search questions to generate new queries and information related to the task

- Updating existing tasks based on new information gathered

- Selecting appropriate sources from all the sources collected

- Summarising sources into a report

Given this reformulation, it becomes easier to define consistency or success. It makes the operating regimes of subproblems easier to understand, letting us define choke points and regions of freedom. Not all parts of a problem space need to be held to the same restrictive set.

Trenches

The next problem to solve is task avalanche, where an increasing task set overwhelms an agent into confusion, along with its operator/designer.

This happens in both vibe-coding style interactive workflows, as well as enterprise agents designed to operate autonomously. They happen in much the same way that pristine codebases turn into huge legacy monsters over time. Here's a recipe:

- An agent is designed to do one thing. Somewhere in the distance, a coding agent is asked to do something.

- They both do it well. Of course, the reward for doing something is to be asked to do more. The agent gets more complex, and the coding agent is asked for something else.

- The agents both grow increasingly erratic and problematic.

- Skynet.

The one more turn feeling is understandable. If we have a working system (code or agentic or chat) it's easy to heap new problems onto it until you reach the pareto optimum for 'sort of works but don't breathe near it wrong' (in a Kafka-esque recreation of the Peter principle). This leads to rot in agentic systems from both directions of the context window.

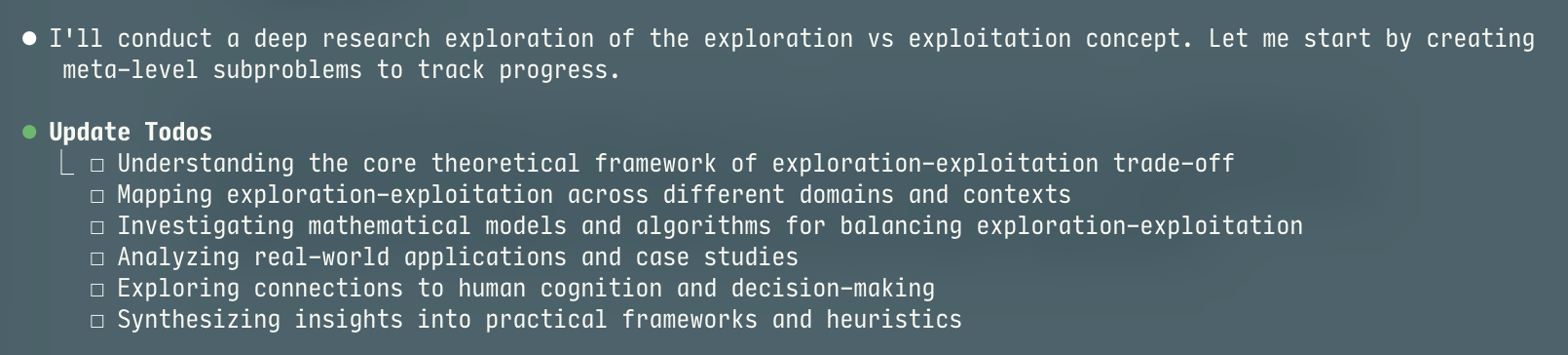

Near the top, prompts start out as clean as the ten commandments, and eventually end up looking like the federal tax code. Down below, more and more tool calls are added to the loop making it suicide worthy to even try figuring out what caused a particular result.

The best way to describe this is worldline rot: an erosion of meaning across the entire context window. The same affects humans; ask any of us with more than a hundred tabs open whether there's some relationship between tabs and cognitive performance degradation.

We found that the only real solution was to dig trenches - hard boundaries between subproblems that make it easier to reason about bounded areas of behavior. Think of them as classes, steps in a workflow, or services. Clearer boundaries between problems forces agent creators (humans) to clarify the context being handed over.

Doing this in practice is a lot like using the borrow checker: significantly harder at first to grok, but anything you build will be more reliable and easier to reason about.

Once you have good trenches, see if you can make the distance between them smaller. Reset state often, and clearly.

Receipts

Here's something I learned over four years of deploying AI systems to users, each one steadily increasing in complexity. When users call something reliable, they mean two things:

- The system does what it does repeatably.

- They agree with the outputs, or think the output is predictable.

There are far more complex definitions of reliability in engineering, but these are the two human measurements I've observed. This is a problem for agentic tasks. While repeatability can be solved by digging good trenches, resetting state, and reformulating problems, doing things correctly has an upper bound that is inversely proportional to complexity.

The reason is what we've come to name the judgement call. A judgement call is a decision that is contested even among humans of the same demographic. As tasks get more and more complex, the number of judgement calls in the run increase proportionately. The number of judgement calls in a run relates to a ceiling on how reliable a system can be, when evaluated by a human.

So it might well be that agents never achieve five nines of reliability. The solution in our case was to aim for five nines of accountability.

What if every character (99.999%) in every intermediate and output could be easily traced to the specific decision, response, source, or script that caused it? What if those things could be traced to the decisions and sources that caused them? How traceable can we make our results?

This is the same approach that made it possible for WalkingRAG to use llava (a first-gen VLM) to decode ships' manuals. Systems of receipts... make it possible to examine decisions and results at runtime, instead of needing to freeze them en masse in evals.

Receipts make up for the agentic gap in reliability in two ways:

- They make it possible for users to empathize with your agents. This is more important than you think. Quite often, users are looking to understand and agree with the agent - especially in problems with lots of judgement calls.

- Receipts make it easier for other AIs to fix problems themselves, often with no real intervention from you.

Here's what receipts tell your users:

The same way that 100% code coverage is often a worthless goal to shoot for, 100% reliability (as defined above) may be impossible. 100% receipts coverage however, is possible and ideal.

Marginalia

Some smaller things that turned out to be important:

Less is more when it comes to tools

Trust me on this. We have now directly compared different numbers of tools, MCPs, routers across different agents and harnesses, and it usually turns out the same way.

An agent equipped with Read, MultiEdit and Shell can do so much more (and do it better) than 20 MCPs that crowd the context window. I'm not the first person to say this, just one among many:

Sherlock Holmes, the Consulting Developer by Stuart Halloway taught me a lot. If you replace this article with this talk, I think you'll be smarter - and I won't mind.

Look for the levers

When working on a problem, know the implications of each change, or at least think about them. Reasoning is a good example. Thinking models (and thinking traces) improve some results, but they also increase confidence in hallucinations and lead to some very persistently wrong claims further down an agentic chain. There are very few free lunches in our world - investigate each toggle and switch you can change.

Benefiting from brittleness

I feel like I'm here to take away all the toys: in some ways, this guide is about applying rigor to a field that has felt like magic. The transition from magic to science however is where things really accelerate.

Once we started putting these things into practice, our agents felt different. Instead of unwieldy complex beasts that only some of us (with the perfect amount of sleep) could wrangle, they became easier to inspect, modify and deploy.

With well formulated subproblems, clean trenches defining context boundaries, and regions of freedom and choke, moments of brittleness - when they happen - were no longer catastrophic failures. They became signals, either for human intervention, or spots that indicated judgement calls and variability in the problem.

Brittleness in the right abstraction is models being allowed to be creative, exposing new capabilities and displaying sparks of true AGI66Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-46Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4. Additionally, you now have solid, consistent sections of agentic progress that can be made fundamental components in a larger, taller stack.

A long time ago, someone well versed in stochastic systems wrote:

There is a crack in everything, that's how the light gets in.

Building systems that don't shatter at the first crack is often about engineering tolerance. Hopefully this piece helps convey what we've learned.