Southbridge has now operated as an AI-native organization for almost a year: we don't just welcome but expect AI enabled work. We do not discriminate between human or artificial intelligences when it comes to output.

Operating in a world of changing models, capabilities, and finding new ways to work, structure our organization, and hire has been challenging. It has been incredibly helpful to learn from other individuals and companies like Dan Pupius and Bryan at Oxide. Here is what we've learned from months of hiring, hundreds of applicants, and the underlying problems we're trying to solve. We're also linking our take-homes below as free to use for employers and free to solve for candidates.

The problem

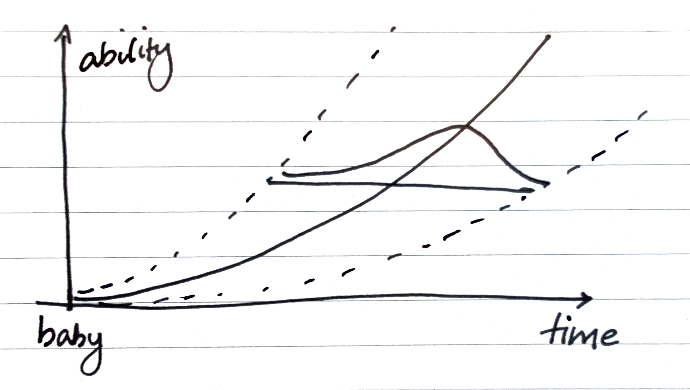

The problem with hiring is the new skill surface. Previously, the skill surface for engineering - and other experience-based professions - looked like this.

In simple terms, humans get better at things the longer we do them. The gradient for how quickly we improve with time under tension tends to be normally distributed, giving us two axes to measure.

Most of the work when it came to hiring (outside of culture-fit) came down to figuring out where someone sat on this graph of performance - and by extension, price to performance - using some kind of process that decides whether a candidate joins the team. Get it wrong, and you waste their time and yours.

This is why software companies have traditionally looked for experience in number of years, with additional screening to figure out candidate-specific position on the normal curve.

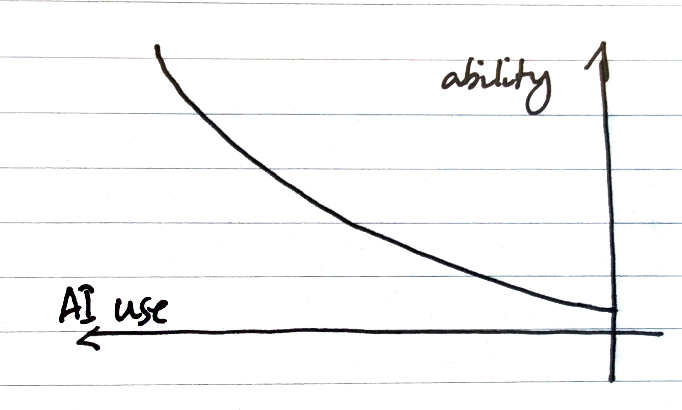

Along comes AI (and agents), and we have a new axis: how AI-enabled you are. Having spoken to a large number of candidates, this is what seems to be the prevailing opinion on how AI use influences performance:

Unfortunately, in all cases we've seen, it looks something like this.

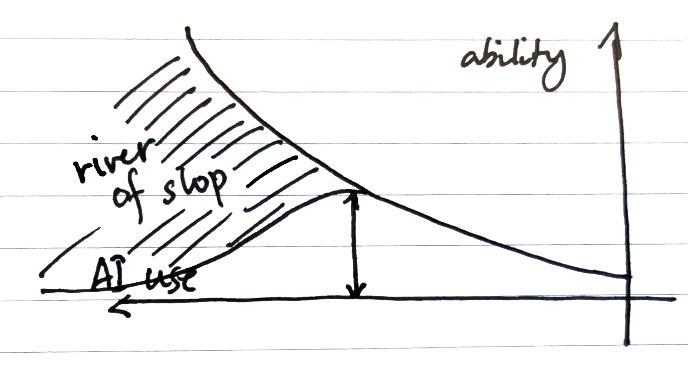

As AI use increases, behaviors creep in that increase slop, to the point where eventually, it's all slop. This is why both sides are right when it comes to the AI good vs bad argument. We now have multiple concrete examples internally of how true performance can 10-50x with the right use of AI, and how you can work an entire day with AI to produce and learn absolutely nothing.

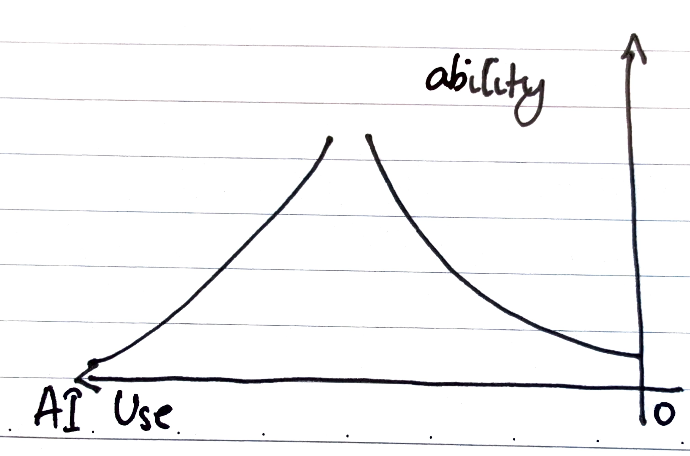

So our true performance surface looks something like this.

On the right side (I apologise for flipping convention, but it makes more sense in English) we have traditional engineers who use next to no AI. On the left, we have the heavily AI-accelerated.

The problem with the right is that you're leaving too much performance on the table. In most professions, the lift offered by general intelligence on tap is too much. The age-old arguments still stand - walking somewhere instead of driving gives you more time for ideas, learning something from a book instead of a web search gives you broader knowledge and a longer attention span, and using a plough instead of a tractor lets you understand how healthy your soil is. As someone who spent part of my childhood at a farm, I can attest.

However, professional work is often about the destination, about getting seeds sown the next day, or a commit finished. If you're too suspicious about using AIs in 2026, I guarantee your methods of working will seem downright epicurean by the end of the year. Yet -

The problem with the left is that you become a human-enabled AI, instead of an AI-enabled human. In a large number of candidates (and myself once upon a time), we're seeing this loss of autonomy and agency that increases with AI use. Through a phenomenon we've come to internally call AI brainrot, at some point too much of the actual thinking and decision making is offloaded to the AI - so much so that your only real purpose is giving the AI existence by pressing enter. You become every stereotype we once had about middle managers, taking credit for work that you barely participated in, with no effort to understand it.

What's wrong with that if the work is done? The problem is that it's not done, not really. Except for a percentage of routine tasks, most knowledge work can seem done without being reliable enough to build on top of. This has been such a problem that we've been forced to make an AI policy where we talk mostly about this (and intent).

The take-home as the sieve, the interview as the winnow

The problem for us - as a tiny, tiny team - is in finding a way to measure candidates on this surface in a way that we can verify more efficiently. This is where the take-home functions for us as the first sieve to balance the sheer volume of applications to our very limited man hours.

However, four times in 2025 we've gone through the process of crafting a take-home only for new models to come out, and for us to drag our take homes into an agent to watch it solve the entire thing.

It has simultaneously been exciting and disheartening, but it's also meant that we've gotten exceedingly good at building new ones, and detecting "AI smells".

So what properties do we want from our take-homes?

- We want to identify where on the AI skill surface an applicant sits. This means a take-home that comes in under 3 hours if you're appropriately AI-enabled, and more if you veer left or right.

- We want them to be easy to review - especially in cases where there isn't a good fit. We want bad work to smell from a mile away so we don't waste time on both sides pushing forward with interviews.

- We want projects that are fun - not needlessly convoluted - and provide an opportunity for candidates to jump off the page.

Writing new take-homes has also been an exercise for us in figuring out what the role of the human really is in the modern engineering pipeline. The truth couldn't be more simple: engineering at Southbridge today is primarily reading and writing, and bottlenecked by English comprehension.

Being better - or getting better - at either reading or writing directly correlates to job performance. Most of our time - including mine - is spent writing specifications, prompts, instructions, documents to the humans and AIs at this company, and reading outputs from the same group of intelligences.

Our interviews now focus exclusively on your ability to read and understand documents and outputs, and to express yourself well - in English - with enough context for your work to be picked up and executed on by a human or AI. As our AI policy has gotten longer - in a weird turn of events - the policy itself has served as an additional sift: candidates that actually read it (instead of using an LLM to substitute the reading) jump ahead of the pack.

If they prove useful

Here's our AI policy: Southbridge AI Policy

Here's our frontend take-home: Frontend Take-Home: Level 2

Here's our backend take-home: Backend Take-Home: Level 2

If any of these end up being helpful, we'd love to know. (If you'd like to apply, reach out with your best results on either of the take-homes!) It has been a strange year as we all rediscover what it means to work and build things, both individually and as part of a team. 2026 so far does not look any less chaotic.